Are we a Christian nation?

No.

Blessed, indeed, is the nation whose God is the LORD. But nations don't have gods these days. People do. Nations don't believe. Nations aren't baptized. People are. Outside of the Muslim world, even nations which have state religions recognize and protect the right of people who believe and practice other ones.

The other day I posted a quotation from John Adams to the effect that ours is no more a Christian nation than it is a Jewish or Muslim one. There are many on the right who- often on the basis of inaccurate or even fabricated quotations from the Founders or entirely too accurate ones from later figures in our national history- dispute that point. There is a whole movement in the Calvinist branch of Protestantism which advocates theonomy, the idea that civic law should be based on God's law. But that idea violates the vision of the Founders. I, as a Lutheran, am also compelled as a matter of conscience to reject it. While we are all subjects of what my tradition calls the Kingdom of the Left Hand- the world God created and governed by laws of justice and equity which are far more the common property of most traditions than either the religious right or the secularist left is willing to admit- specifically sectarian religion is not the basis of our national life. To be sure, specific and sectarian religion (and other philosophies) must exist and have something to contribute to our national dialog and debate precisely because we as a people are an aggregate of many specific beliefs and philosophies, and we can't really say much of substance to each other apart from them.

Someone asked me for a source for the quotation. It seems that President Adams said it when commenting on the Treaty of Tripoli, which he submitted to the Senate in 1797. It established American's first formal alliance with a foreign power- a Muslim one! Article XI of that treaty states,

The First Amendment, of course, says, "Congress shall pass no law regarding an establishment of religion, nor prohibiting the free exercise thereof." Article VI of the Constitution prohibits any religious test for public office.

Adams's predecessor, George Washington, received a letter from members of Yeshuat Israel Synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island, which stated,

Washington replied,

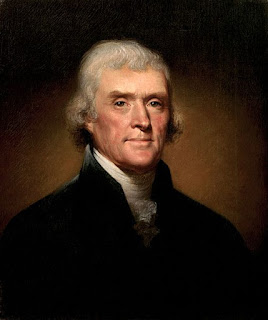

Both sides seem to miss major points in the attitude of the Founders toward religion. The right accepts as an article of faith that the United States is in some sense a Christian nation, in part because there are some quotes from relatively early figures in our history which make that argument and partially because of intellectual laziness. But ultimately I think the reason is an overextension of a legitimate point which the contemporary left completely misses, but which Jefferson and other Enlightenment figures understood quite well.

Ultimately there are only two theories of the origin and basis of governmental power and legitimacy. The first, and by far the most common, is the notion that, in the words of Mao, "Power flows from the barrel of a gun." Essentially this is the view that might makes right, that those in power have the natural right to call the shots, and that any "rights" which individuals which individuals have are in fact merely privileges granted by the generosity of those in power and can be withdrawn at any time by the whim of those who extended them. The Divine Right of Kings is based on this principle, and ironically so is the governmental philosophy of collectivist Marxist regimes, which use populist or class-based rhetoric as a disguise for what boils down to the same thing.

n China, this took an interesting form: the basis of government was said to be the "mandate of Heaven." Those who rule do so because the universe has so decreed; if they lose power, it's because "heaven" has withdrawn its "mandate" and granted it instead to someone else. In theory, it's simply a supernaturalized version of the same thing: the idea that those in power have a right to it simply because the universe has given it to them.

Biblical and early Christianity isn't really interested in the question beyond the notion that "the powers that be are ordained by God" and ought to be obeyed on that basis. This tends to support the notion that the powerful by definition have a right to power, but the Christian version includes a somewhat subversive element: the idea that those who rule don't simply do so because might makes right. Rather, like the traditional Chinese idea, early Christianity maintained that it isn't the mere fact of power which is self-legitimizing, but rather the notion that a supernatural power above and beyond those who rule has granted the privilege to those who exercise it. This contains the seeds of the notion that it is therefore accountable to that power (it would be an interesting subject which I haven't studied much, but I suspect that at least in theory Judaism would say the same thing, although in the Diaspora it was seldom a relevant subject). But the principle remained undeveloped in the Early Church because Christianity was an apocalyptic religion which- as Christ intended- expected the Parousia and God's direct rule to supervene at any moment.

Now, here's the crucial point which the left misses: the Enlightenment clearly understood that if rights were to be anything but privileges on loan from the powerful, they had to have their origin in an authority to whom the powerful were accountable. That's the reason why consistent, classical, outright atheism was relatively rare in at least the public philosophy of Enlightenment authors; Deism (the notion that there exists a God, usually a vague and ill-defined one, who created the universe, instituted natural laws, and then set the machine running under its own power and just watched things unfold) was much more common.

Thus, in the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson wrote that the Americans "hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, --That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness." Christianity certainly wouldn't approve of the revolutionary principle because it counseled apocalyptic indifference to what it regarded as a temporary order of things. That's where the God (or god) of the Founders differs from the God of Christianity. But the Enlightenment clearly saw that only if society acknowledged if only for the purpose of its philosophical basis, the existence of a deity could human rights truly be rights and not mere privileges on loan from those in power.

That's why religion (as opposed to "Church," or differentiated and institutionalized religion) can't be totally separated from the State. And history records that most of the important social changes in America have taken place due to movements that were, in fact, religious in origin: the Abolitionist movement, the Civil Rights movement, the movement against child labor,, the anti-war movement during Vietnam, and in England the movement to abolish the slave trade. Religion in general and ethics are certainly not identical, but they tend to be related. You can't get rid of public religion.

Another thing the left misses is that our legal tradition- and in fact, the legal tradition of the West in general- is deeply rooted in religion. I have to disagree with the Supreme Court: I think it's perfectly legitimate to post the Ten Commandments in a courthouse, not as a religious text but for the same reason the Magna Carta would be appropriate in an American courthouse. They're a historical legal document that had an important impact on the development of our legal tradition, and I don't see how acknowledging that violates either the spirit or the letter of the First Amendment.

But our public religion is not Christianity or Judaism. It's vague, unspecific, and extends only to the theoretical basis of our government. Beyond that diversity of belief is our governing theory. Our public discourse shouldn't exclude religion; in fact, it should encourage the interplay of religious ideas as well as purely secular ones in the public square, always with the awareness that we as a people don't endorse any individual religion but are interested in what all of them have to say.

President Eisenhower somewhat infamously said that good government depends on the input of religion and that he didn't care which one. As a Christian, I am very nervous about the American Civil Religion which Will Herberg and Paul Murray Cuddihy wrote about (Cuddihy's NO OFFENSE ought to be read by every American who is serious about religion in the public square). It's important to realize that "nature and nature's God" is NOT the Holy Trinity, and neither is the kindly, indulgent, and slightly senile deity most Americans think of when they hear the word "God." As a Lutheran, I'm concerned about the tendency of the Right to keep in mind (or even be aware of) Luther's concept of the Two Kingdoms. As a Missouri Synod Lutheran, I'm uncomfortable with interfaith services (despite the fact that I may be going to one tonight) precisely because the god of the lowest common denominator who is worshipped there is not my God- and not that of my Reformed or Catholic or Jewish or Muslim neighbor, either.

But the whole subject is a great deal more complicated than either the right or the left seems these days to understand. Our ideal in America is not that a specific religion should characterize us as a people, and nor is it that religion should be excluded from the public square. It's that everybody- ALL religions and philosophies- should have an equal voice, with none excluded and favored, and that we as a people should weigh the input of all of them in making our decisions.

Blessed, indeed, is the nation whose God is the LORD. But nations don't have gods these days. People do. Nations don't believe. Nations aren't baptized. People are. Outside of the Muslim world, even nations which have state religions recognize and protect the right of people who believe and practice other ones.

The other day I posted a quotation from John Adams to the effect that ours is no more a Christian nation than it is a Jewish or Muslim one. There are many on the right who- often on the basis of inaccurate or even fabricated quotations from the Founders or entirely too accurate ones from later figures in our national history- dispute that point. There is a whole movement in the Calvinist branch of Protestantism which advocates theonomy, the idea that civic law should be based on God's law. But that idea violates the vision of the Founders. I, as a Lutheran, am also compelled as a matter of conscience to reject it. While we are all subjects of what my tradition calls the Kingdom of the Left Hand- the world God created and governed by laws of justice and equity which are far more the common property of most traditions than either the religious right or the secularist left is willing to admit- specifically sectarian religion is not the basis of our national life. To be sure, specific and sectarian religion (and other philosophies) must exist and have something to contribute to our national dialog and debate precisely because we as a people are an aggregate of many specific beliefs and philosophies, and we can't really say much of substance to each other apart from them.

Someone asked me for a source for the quotation. It seems that President Adams said it when commenting on the Treaty of Tripoli, which he submitted to the Senate in 1797. It established American's first formal alliance with a foreign power- a Muslim one! Article XI of that treaty states,

As the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion,—as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion, or tranquility, of Mussulmen [Muslims],—and as the said States never entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mahometan [Mohammedan] nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries.

The First Amendment, of course, says, "Congress shall pass no law regarding an establishment of religion, nor prohibiting the free exercise thereof." Article VI of the Constitution prohibits any religious test for public office.

Adams's predecessor, George Washington, received a letter from members of Yeshuat Israel Synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island, which stated,

Deprived as we heretofore have been of the invaluable rights of free Citizens, we now (with a deep sense of gratitude to the Almighty disposer of all events) behold a Government, erected by the Majesty of the People—a Government, which to bigotry gives no sanction, to persecution no assistance—but generously affording to All liberty of conscience, and immunities of Citizenship: deeming every one, of whatever Nation, tongue, or language, equal parts of the great governmental Machine…

Washington replied,

While I received with much satisfaction your address replete with expressions of esteem, I rejoice in the opportunity of assuring you that I shall always retain

grateful remembrance of the cordial welcome I experienced on my visit to Newport from all classes of citizens.

The reflection on the days of difficulty and danger which are past is rendered the more sweet from a consciousness that they are succeeded by days of uncommon prosperity and security.

If we have wisdom to make the best use of the advantages with which we are now favored, we cannot fail, under the just administration of a good government, to become a great and happy people.

The citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for having given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy—a policy worthy of imitation. All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship.

It is now no more that toleration is spoken of as if it were the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights, for, happily, the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.

It would be inconsistent with the frankness of my character not to avow that I am pleased with your favorable opinion of my administration and fervent wishes for my felicity.

May the children of the stock of Abraham who dwell in this land continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants—while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree and there shall be none to make him afraid.

May the father of all mercies scatter light, and not darkness, upon our paths, and make us all in our several vocations useful here, and in His own due time and way everlastingly happy.

Both sides seem to miss major points in the attitude of the Founders toward religion. The right accepts as an article of faith that the United States is in some sense a Christian nation, in part because there are some quotes from relatively early figures in our history which make that argument and partially because of intellectual laziness. But ultimately I think the reason is an overextension of a legitimate point which the contemporary left completely misses, but which Jefferson and other Enlightenment figures understood quite well.

Ultimately there are only two theories of the origin and basis of governmental power and legitimacy. The first, and by far the most common, is the notion that, in the words of Mao, "Power flows from the barrel of a gun." Essentially this is the view that might makes right, that those in power have the natural right to call the shots, and that any "rights" which individuals which individuals have are in fact merely privileges granted by the generosity of those in power and can be withdrawn at any time by the whim of those who extended them. The Divine Right of Kings is based on this principle, and ironically so is the governmental philosophy of collectivist Marxist regimes, which use populist or class-based rhetoric as a disguise for what boils down to the same thing.

n China, this took an interesting form: the basis of government was said to be the "mandate of Heaven." Those who rule do so because the universe has so decreed; if they lose power, it's because "heaven" has withdrawn its "mandate" and granted it instead to someone else. In theory, it's simply a supernaturalized version of the same thing: the idea that those in power have a right to it simply because the universe has given it to them.

Biblical and early Christianity isn't really interested in the question beyond the notion that "the powers that be are ordained by God" and ought to be obeyed on that basis. This tends to support the notion that the powerful by definition have a right to power, but the Christian version includes a somewhat subversive element: the idea that those who rule don't simply do so because might makes right. Rather, like the traditional Chinese idea, early Christianity maintained that it isn't the mere fact of power which is self-legitimizing, but rather the notion that a supernatural power above and beyond those who rule has granted the privilege to those who exercise it. This contains the seeds of the notion that it is therefore accountable to that power (it would be an interesting subject which I haven't studied much, but I suspect that at least in theory Judaism would say the same thing, although in the Diaspora it was seldom a relevant subject). But the principle remained undeveloped in the Early Church because Christianity was an apocalyptic religion which- as Christ intended- expected the Parousia and God's direct rule to supervene at any moment.

Now, here's the crucial point which the left misses: the Enlightenment clearly understood that if rights were to be anything but privileges on loan from the powerful, they had to have their origin in an authority to whom the powerful were accountable. That's the reason why consistent, classical, outright atheism was relatively rare in at least the public philosophy of Enlightenment authors; Deism (the notion that there exists a God, usually a vague and ill-defined one, who created the universe, instituted natural laws, and then set the machine running under its own power and just watched things unfold) was much more common.

Thus, in the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson wrote that the Americans "hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, --That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness." Christianity certainly wouldn't approve of the revolutionary principle because it counseled apocalyptic indifference to what it regarded as a temporary order of things. That's where the God (or god) of the Founders differs from the God of Christianity. But the Enlightenment clearly saw that only if society acknowledged if only for the purpose of its philosophical basis, the existence of a deity could human rights truly be rights and not mere privileges on loan from those in power.

That's why religion (as opposed to "Church," or differentiated and institutionalized religion) can't be totally separated from the State. And history records that most of the important social changes in America have taken place due to movements that were, in fact, religious in origin: the Abolitionist movement, the Civil Rights movement, the movement against child labor,, the anti-war movement during Vietnam, and in England the movement to abolish the slave trade. Religion in general and ethics are certainly not identical, but they tend to be related. You can't get rid of public religion.

Another thing the left misses is that our legal tradition- and in fact, the legal tradition of the West in general- is deeply rooted in religion. I have to disagree with the Supreme Court: I think it's perfectly legitimate to post the Ten Commandments in a courthouse, not as a religious text but for the same reason the Magna Carta would be appropriate in an American courthouse. They're a historical legal document that had an important impact on the development of our legal tradition, and I don't see how acknowledging that violates either the spirit or the letter of the First Amendment.

But our public religion is not Christianity or Judaism. It's vague, unspecific, and extends only to the theoretical basis of our government. Beyond that diversity of belief is our governing theory. Our public discourse shouldn't exclude religion; in fact, it should encourage the interplay of religious ideas as well as purely secular ones in the public square, always with the awareness that we as a people don't endorse any individual religion but are interested in what all of them have to say.

President Eisenhower somewhat infamously said that good government depends on the input of religion and that he didn't care which one. As a Christian, I am very nervous about the American Civil Religion which Will Herberg and Paul Murray Cuddihy wrote about (Cuddihy's NO OFFENSE ought to be read by every American who is serious about religion in the public square). It's important to realize that "nature and nature's God" is NOT the Holy Trinity, and neither is the kindly, indulgent, and slightly senile deity most Americans think of when they hear the word "God." As a Lutheran, I'm concerned about the tendency of the Right to keep in mind (or even be aware of) Luther's concept of the Two Kingdoms. As a Missouri Synod Lutheran, I'm uncomfortable with interfaith services (despite the fact that I may be going to one tonight) precisely because the god of the lowest common denominator who is worshipped there is not my God- and not that of my Reformed or Catholic or Jewish or Muslim neighbor, either.

But the whole subject is a great deal more complicated than either the right or the left seems these days to understand. Our ideal in America is not that a specific religion should characterize us as a people, and nor is it that religion should be excluded from the public square. It's that everybody- ALL religions and philosophies- should have an equal voice, with none excluded and favored, and that we as a people should weigh the input of all of them in making our decisions.

Comments